At one point in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? Sidney Poitier, the African-American husband-to-be, tells Spencer Tracy, the father-of-the-bride, how their potential children may become Presidents of the United States. Poitier, lightening the mood, acknowledges that he’ll accept Secretary of State – of course, his wife-to-be is possibly too ambitious. Made in 1967, it seems the filmmakers weren’t too ambitious, and only six years prior to the cinema release date, in Kapiʻolani Maternity & Gynecological Hospital in Honolulu, Hawaii, Barack Hussein Obama II was born. It is difficult to imagine the era in fact. We know the horror stories and the necessity of the civil rights movement, depicted recently in Ava DuVernay’s Selma. But, born into a racially intolerant world, it is difficult to comprehend the abuse that afflicted the black populace of America. Bear in mind that, while the film was in cinemas, Martin Luther King was assassinated. This was a different time.

A taboo topic, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? introduces Joanna Drayton (Katherine Houghton) hopping off a plane with her lover Dr. John Wayde Prentice Jr (Poitier). They talk casually about the inevitable shock her parents (Hepburn and Tracy, ending a nine-film run together) will receive. Mrs Drayton is shocked but accepting, while Mr Drayton is more concerned. Crucially for their safety – and the inevitable abuse their child would receive. The final act introduces John’s parents also, who are equally concerned about the future. The maid, Tilly (Isabel Sanford), is vocal about her frustrations, explaining how she dislikes anyone who is acting ‘above himself’. Director Stanley Kramer jumps from couples sparring and awkward group moments comfortably. Though clearly structured to emphasise the various opinions and positions taken, he resolves the film comfortably with a finale that accepts change, albeit without all parties agreeing on the issue – but a sense that, in time, they will.

Inevitably perhaps, watching within the 21st Century, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? seems awfully twee, and reeks of a sentimentality that is simply at odds with our current perspective. The reason the interracial marriage wins over the bride’s father is because they’re “in love” - something clear from the outset, but it takes him the duration to accept. Star performances from Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier and (the BFI season dedicated to) Katherine Hepburn are outstanding, and full of warmth. The film was Tracy’s last (dying only 17 days after production) and, in one scene, the final monologue took six days to shoot. It is clearly a small-scale film, and it could easily be a play off-Broadway rather than appearing on the silver screen. But its message is clear – change is coming and your masculinity, traditional expectations and fear won’t stop the glorious future that waits.

This is what makes cinema endlessly fascinating. For all its flaws, this is a moment in history. Spencer Tracy’s final film captures attitudes in an era that I, for one, wasn’t present for. Imagine if cinema was available as an art form during the French Revolution – what conversations and situations would be presented? The last 100 years of cinema has meant that every momentous, historical occasion has a library of films that run alongside the event. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? joins In the Heat of the Night and To Kill a Mockingbird as key films in an era that changed the future of the western world.

This post was originally written for Flickering Myth in March 2015

Saturday 21 March 2015

Wednesday 11 March 2015

The Tales of Hoffmann (Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger, 1951)

"I have to say”, says Director Michael Powell prior to working on The Tales of Hoffmann, “I didn’t know much about the opera”. That makes both of us Mr Powell. On Extended Run at the BFI this month is the Technicolor triptych-narrative, The Tales of Hoffmann. Released in 1951, this was made three years after Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s celebrated masterpiece The Red Shoes. Rather than incorporating dance into a story, Powell and Pressburger decided to adapt a full performance in its entirety, presenting an epic story of romance, lost-love and tragedy.

In the interval of a ballet, Hoffmann (Robert Rounseville) regales a crowd with talk of his previous exploits. Drunkenly holding court, he tells of his first romance with an automaton (Moira Shearer/Dorothy Bond), whereby he’s required to wear glasses to see her come to life. This seeps into the second Venetian story, a devilish tale whereby a dark-haired seductress (Ludmilla Tchérina/Margherita Grandi) manages to charm his attention and steal his reflection. After a fight with her true lover (Robert Helpmann/Bruce Dargavel always playing the villain), he regains his mirrored-self but escapes, only to meander into his third story in Greece. His final romance is with a dying singer (Ann Ayars). Her singing is what’s killing her, but her voice is what makes them happy. A corrupt doctor directs her voice and, inevitably, she dies. Returning to Hoffmann’s story-telling, we see his current love (also Moira Shearer) witness the drunken consequence, as he lays passed out on the table, so she leaves with his nemesis into the night.

This recent restoration was by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, with supervision by Martin Scorsese, the magnificent editor Thelma Schoonmaker Powell and Ned Price. Scorsese’s kudos will reach wide, and the influence of Powell and Pressburger’s grand filmmaking can be seen in many of his films, especially Shutter Island and Hugo. Glorious use of colour and dreamlike landscapes are simply mesmerising, carrying you away to a faraway land that we rarely see in cinema. The Red Shoes managed to capture that surrealist perspective that dominates the story in a single dance-sequence, while the magical opera-singing and out-of-this-world context in The Tales of Hoffmann only serves as a catalyst to exploit these dreamy notions further.

Each story is unique and linked to a specific colour palette. The yellowed ‘Olympia’ story establishes Hoffmann as gullible and the sequence toys with his desperation for love. Each arrangement reveals different vices – and virtues – of Hoffmann. Moira Shearer is outstanding in her mechanical form, shuddering to a stop, before being wound up again. Hoffmann’s clown-friend, Nicklaus (Pamela Brown/Monica Sinclair) balances the seriousness, as her glances to camera expose her frustration, presented as ‘I-give-up-with-this-guy’ shrugs. When the palette shifts to the lustful, passionate red in Venice, mass orgies and occult-magic shift the tone, but the message seems similar: Hoffmann gives his love freely to Giulietta, at a high cost. Nicklaus again, stands idly at the side, resigned to observe foolish decisions. The final story holds the biggest heart, and the clown rarely interrupts. Antonia is good, and loving. The calmness of the blue resonate a sense of peace and hope in the story. Though, as the music builds, and the crescendo is loud, we know all will end in tears.

This is not an easy watch, but it is unforgettable. Zombie-extraordinaire George A. Romero stated in 2002 that it was his favourite film of all-time – in fact, it is “the film that made him want to make movies”. Scorsese and Romero have seen something unique. Something so grand, and beautiful, that maybe only a directors-eye can truly appreciate. There is an argument that will defend the stage – why should we watch the film when the experience in the theatre will surely be superior. I’m not so sure. Powell’s ambitious direction, his vivid sets and extraordinary editing is innovative and breath-taking. One dance is shown from four different perspectives in the same shot. The dual characters are fun, but even more fascinating as one character takes off a mask to reveal himself again, and then another mask and a different character, played by the same actor. For 1951, this must’ve been terrific – and it remains terrific today.

This post was originally written for Flickering Myth

Monday 9 March 2015

A Film a Day: Reflections on February

This was the month I had to carefully consider what ‘counts’ as a film? Despite its appearance on Letterboxd, does Power/Rangers really count? It’s a short, fan-made film and opening up that box of wonders would mean that cheeky takes on established properties (Troops, Mortal Kombat: Rebirth, etc) could all be considered fair game. I could rack up my numbers in an afternoon, and sleep soundly in the knowledge that I’d reach my target at the end of the year. Alas, I’ve had to draw a line through these and actively make my life more difficult.

Always Make Notes

It’s very easy to casually let a film play and ‘count’ the film. But digesting, and letting your brain ruminate on the themes, thoughts and ideas is part of the experience. Over the course of two days, I watched Harold and Maude and CitizenFour. Both completely different, and equally outstanding in their own unique ways. But I forgot to write my note cards. I have the cards, with the title scrawled on the top, ready for my further opinions – but without the views written down, I have to remind myself of those initial feelings. I discussed CitizenFour at length with my wife, but after watching Harold and Maude on my own, it is easy to lose track of what I was thinking. Of course, they’ll come back to me if I swot up by reading coverage elsewhere. But with a film a day, it isn’t long before the next day rolls on and I’m immediately thinking of something else.

Length Counts

In February, I watched Shoah and Night and Fog. Both are documentaries exploring the horrors of the holocaust. The former directed by Claude Lanzmann and the latter by Alain Resnais. Shoah shows no footage whatsoever of the liberation or atrocities within the camps while Night and Fog explicitly shows the gruesome detail. Crucially, in the context of my Film-a-Day viewing habits, Shoah is a 9-hour sprawling epic, while Night and Fog is barely 30-mins. Both appear in the Top 5 of Sight & Sound’s Best Documentaries of All-Time. But this idea of the length of a film to ‘count’ comes into question. I think the credibility comes into question also and, Night and Fog clearly required note-taking and reflection as any film would. Shoah knocked out days at a time because of its length and, though I can’t claim it counts for anything more than one, arguably its scale should come into question. A little freedom is necessary – if its importance is unequivocal then it ‘counts’. Alternatively, India’s Daughter, a bold and defiant call to arms for gender equality following the rape and murder of Jyoti Singh holds equal weight and therefore remains included. As mentioned, Power/Rangers does not count.

Set some goals…

Due to the recent release of Life of Riley (Alain Resnais’ final film), I felt that I needed to swot up on Alain Resnais. This meant a speedy purchase of Last Year at Marienbad and Hiroshima mon amour and a sneaky hunting down of the aforementioned Night and Fog. I forced myself to watch these films, and it ensured that I didn’t spend time endlessly scrolling through Netflix or desperately checking run-times to see that they could be squeezed in. I’m also keeping track of the upcoming decent films appearing on Netflix. Let’s be honest, there are films you don’t care to watch and have no need to see. But then Frank, Calvary and Zero Dark Thirty appear and you’re set. These pre-determined lists really make sure you don’t waste time selecting and instead get you started sooner.

I also have to thank Ryan McNeil of The Matinee from forcing a last minute switch from Lena Dunham’s Tiny Furniture to How Green Was My Valley. Yeah, It’s unlikely I’ll ever watch the Welsh coal-miner’s Best Picture winner again but it’s ticked off at least. Tiny Furniture will come round again. April isn’t far around the corner, with the fifth series of Game of Thrones and the final part of Mad Men to juggle amongst the films – but if I can do Shoah and House of Cards, it can’t be too difficult. The problem with March though is the likes of Better Call Saul … and a less-structured break at the end of the month with family wedding. I feel I need to bank some movies…

Follow my film-watching habit on Letterboxd: http://letterboxd.com/simoncolumb/ and read my previous notes on watching a film a day in January here

Friday 6 March 2015

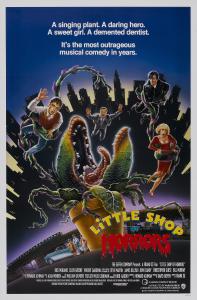

Little Shop of Horrors (Frank Oz, 1986)

In an era whereby Avenue Q and Book of Mormon dominate the musicals on the West End, we mustn’t forget the imaginative and darkly joyous cult favourite Little Shop of Horrors. In fact, Little Shop of Horrors boasts the master duo of Alan Menken and Howard Ashman penning the lyric and music respectively. These are the force that pulled Disney from the dumps and to the heights of The Little Mermaid, Aladdin and Beauty and the Beast only a few years later. Little Shop of Horrors is a feast to devour, and you’d be foolish not to give it a taste.

Seymour (Rick Moranis) works, and lives, on Skidrow. He is madly in love with busty colleague Audrey (Ellen Greene) and despite the abuse he receives from flower-shop owner Mr Mushnik (Vincent Gardenia), he appreciates the roof provided. This is a self-proclaimed rock-horror musical akin to the wickedly delightful Rocky Horror Picture Show. Its B-Movie story is taken straight from a 1960, Roger Corman farce and manages to weave its memorable melodies (including favourites Skidrow (Downtown), Suddenly Seymour and Academy Award nominee Mean Green Mother from Outer Space) seamlessly into the monster-munching narrative. The animation of ‘the plant’, named Audrey II, is flawless as Levi Stubbs provides fast-talkin’ vocals that the puppeteers cleverly navigate. This director’s cut is a real wonder to watch at the cinema too, with a spectacular finale that reverses the original ‘happy’ ending with a special-effects savvy anti-ending with only the destruction of the world in sight – a treat that has only been available since 2012.

Watching Little Shop of Horrors also reveals cameos from the cream of the crop of American comedians in the 1980’s. Bill Murray, James Belushi, John Candy and Steve Martin all make exceptional, memorable appearances. Rick Moranis, a staple of the eighties within Ghostbusters and Honey I Shrunk the Kids, is rarely seen today and the little shop really does make you miss his wide-eyed helplessness that make his characters so much fun.

Little Shop of Horrors manages to make light of a broad range of incredibly dark subjects, whether it is the abusive boyfriend of Audrey, Seymours suicide attempt or the gross poverty of an inner-city. Audrey II represents much more than an entertaining, wise-cracking monster. Audrey II could be consumerism, and our own addiction to shopping and products. Could the plant be about vices? About our struggle to control our urges - no matter how destructive the consequences? In fact, Audrey’s song Somewhere That’s Green alludes to this dreamy sense of happiness. She wants Seymour and she wants to be happy – but the Better Homes magazine is what instructs and describes her happiness. She needs a shiny, chrome toaster and a Tupperware seller to know who she is – and to prove her pleasure. But Audrey is quite clearly played as a ditzy blonde, and surely not the peak of forward-thinking womanhood. Furthermore, the success of the off-Broadway show in 1982 connects the film to Nixon’s presidency, whereby bit-by-bit, the corporate American Dream convinced many - but left many more behind in the gutter (a literal gutter, opposed to ‘The Gutter’ club where Audrey met her boyfriend).

This is a wonderful success, managing to balance cheeky-songs, potentially-poignant subtext and a cast that defines the era it was made within. Little Shop of Horrors plays as part of the BFI’s ‘Cult’ strand that began in January. The experience of watching the ‘Directors Cut’ of Little Shop shows how unique these screenings are – and you can bet they’ll be many more in the coming year. Audrey II’s famous phrase “feed me!” only seems appropriate when treats like this are on the platter every month.

Seymour (Rick Moranis) works, and lives, on Skidrow. He is madly in love with busty colleague Audrey (Ellen Greene) and despite the abuse he receives from flower-shop owner Mr Mushnik (Vincent Gardenia), he appreciates the roof provided. This is a self-proclaimed rock-horror musical akin to the wickedly delightful Rocky Horror Picture Show. Its B-Movie story is taken straight from a 1960, Roger Corman farce and manages to weave its memorable melodies (including favourites Skidrow (Downtown), Suddenly Seymour and Academy Award nominee Mean Green Mother from Outer Space) seamlessly into the monster-munching narrative. The animation of ‘the plant’, named Audrey II, is flawless as Levi Stubbs provides fast-talkin’ vocals that the puppeteers cleverly navigate. This director’s cut is a real wonder to watch at the cinema too, with a spectacular finale that reverses the original ‘happy’ ending with a special-effects savvy anti-ending with only the destruction of the world in sight – a treat that has only been available since 2012.

Watching Little Shop of Horrors also reveals cameos from the cream of the crop of American comedians in the 1980’s. Bill Murray, James Belushi, John Candy and Steve Martin all make exceptional, memorable appearances. Rick Moranis, a staple of the eighties within Ghostbusters and Honey I Shrunk the Kids, is rarely seen today and the little shop really does make you miss his wide-eyed helplessness that make his characters so much fun.

Little Shop of Horrors manages to make light of a broad range of incredibly dark subjects, whether it is the abusive boyfriend of Audrey, Seymours suicide attempt or the gross poverty of an inner-city. Audrey II represents much more than an entertaining, wise-cracking monster. Audrey II could be consumerism, and our own addiction to shopping and products. Could the plant be about vices? About our struggle to control our urges - no matter how destructive the consequences? In fact, Audrey’s song Somewhere That’s Green alludes to this dreamy sense of happiness. She wants Seymour and she wants to be happy – but the Better Homes magazine is what instructs and describes her happiness. She needs a shiny, chrome toaster and a Tupperware seller to know who she is – and to prove her pleasure. But Audrey is quite clearly played as a ditzy blonde, and surely not the peak of forward-thinking womanhood. Furthermore, the success of the off-Broadway show in 1982 connects the film to Nixon’s presidency, whereby bit-by-bit, the corporate American Dream convinced many - but left many more behind in the gutter (a literal gutter, opposed to ‘The Gutter’ club where Audrey met her boyfriend).

This is a wonderful success, managing to balance cheeky-songs, potentially-poignant subtext and a cast that defines the era it was made within. Little Shop of Horrors plays as part of the BFI’s ‘Cult’ strand that began in January. The experience of watching the ‘Directors Cut’ of Little Shop shows how unique these screenings are – and you can bet they’ll be many more in the coming year. Audrey II’s famous phrase “feed me!” only seems appropriate when treats like this are on the platter every month.

Labels:

1986,

Bill Murray,

Frank Oz,

Little Shop of Horrors,

Rick Moranis,

Steve Martin

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)